My Owl

Here his vanity was gratified by seeing his portrait at the Dudley exhibition. "

Abigail May Alcott Nieriker

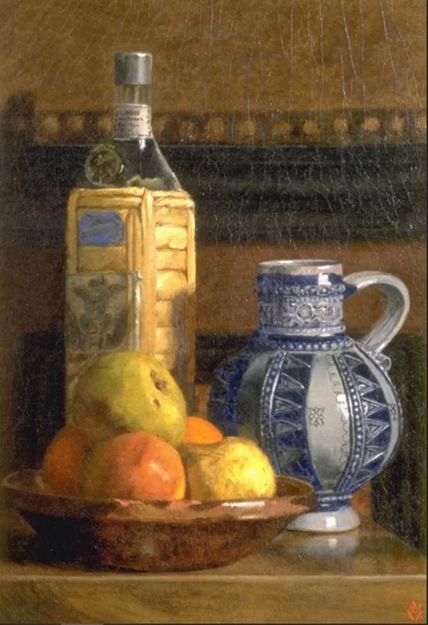

Still Life with Fruits and Bottle by May Alcott Nieriker, 1877. Oil on canvas. Used by permission of Louisa May Alcott's Orchard House

Still Life with Fruits and Bottle by May Alcott Nieriker, 1877. Oil on canvas. Used by permission of Louisa May Alcott's Orchard HouseIntroduction to My Owl by Abigail May Alcott Nieriker

Abigail May Alcott Nieriker's (hereafter referred to as May) progressive family life influenced her varied writing styles and motivated her aspirations, ultimately shaping the plot of My Owl. Particularly, her solo travels in Europe could explain why she personified a taxidermy owl in the manuscript as a manifestation of her ongoing search for companionship.

Biographical Background

Throughout her life, May was primarily taught art by men (Flint and

Hehmeyer xiv), perhaps explaining why her narrative has such an

authoritative tone. The educational opportunities required to produce

My Owl were limited for Nineteenth Century women but

considering the emphasis on the value of education and denial of

social norms in May's family, it is not surprising that she

composed such a story. For example, her mother,

Abigail (Abba) May Alcott, encouraged the Alcott

sisters to keep diaries, which she believed taught her children how

to feel and to

think justly, and to express their thoughts and feelings clearly and

forcibly

(Ticknor 25). May's family eventually settled at

Concord, Massachusetts, a hub of literature and

transcendentalist thinking but isolated for May

in terms of Art (maybe motivating her later art studies in Europe).

The parting from her sister,

Louisa May Alcott, and Concord, meant that May

could experience life as a woman in Europe on her own trying to

establish a career in Art (the basis for My Owl).

It was in when May successfully submitted a still life painting to the Paris Salon. This painting enabled her to become an established artist and would explain how she conveys the feeling of acceptance and progress so vividly in My Owl. Combining her experiences as a solo artist with the background of her scholarly family in which she was raised, May could write a manuscript like My Owl, channelling her standpoint in society through a piece of writing. My Owl depicts this in the story with its autobiographical depiction of a woman striving to be successful on her own, and how this (facilitated through the owl) brings her love and marriage. May represents the woman of her time, the day-to-day woman living how she wanted to live.

Creative Career

As Dabbs notes, women artists in the Nineteenth Century suffered an

institutional deficit

(Dabbs

Empowering 2). This arose from a lack of accessible

tutelage in artistry, along with the inability of female artists to

cultivate and sustain artistic networks like their male peers. This

led to the philosophical realms of genius in art being inherited

solely by men. Overall, the middle-class female artist was doomed to

a corpus of forgotten works. This deficit, however, is what makes the

work of May so extraordinary. The propensity of May's works to

confront the standards set by the academy can be witnessed a

multitude of times in the construction of My Owl. May

understood the importance of travel for any artist and explores its

significance for the female artist in the manuscript; as not simply a

social accomplishment, but a tool with which to sharpen their senses.

May challenged the standards of the social fabric under which she

worked. Although she expressed [timidity] about

beginning

(Alcott and Nieriker 69) in fine arts when in Paris,

her 1877 entry to the Paris Salon was described by Fink as being hung

so low as to almost be on the line

(a

prestigious position indeed) (379). May understood travel as a means

of empowerment; the independence and subtle artistic commentary in

her Turner copies earned praise from

John Ruskin, although copyism was considered

artistically inferior in the art world.

Her marriage to Ernest Nieriker a year before her passing demonstrates how May epitomises the Nineteenth Century woman artist. In taking her husband's name (and using it to establish herself), May obeyed societal convention; however, being sixteen years his senior, May defied it. May's interweaving of experience with imagination defied the philosophical claim that originality must be born of newness; rather, as shown in the manuscript through her presentation of the owl as a companion and friend, May adopted her genius through nuance.

May was among the first wave of artists to dignify the Black portrait

in the Nineteenth Century. Following emancipation, the Black portrait

was often undignified and incorporated such insensitive stereotypes

as watermelon fruit and minstrel-like features, exaggerated for the

comic value of white consumers. This imagery made the Black image

salable

(McElroy xxxii). May, while still

existing within a majority white space and moving within

overwhelmingly caucasian circles, defied the institutionalised

bigotry of her time. Her portrait of a Black woman (see image) is

both dignified and pure; she held a proverbial mirror to the

societies and circles of both art and morality in which she resided.

Symbolism

It is evident that the owl is of utmost importance in symbolism. Though the symbol of the owl is subjective based on one's individual interpretation of the owl, there are two common reading paths that readers may follow. One example of symbolism is the idea that the owl represents the importance of befriending oneself, on such a daunting journey. As the protagonist is alone for most of the plot, they turn inwards to provide themselves with emotional support. The owl serves as a mirror of the protagonist, reflecting the company that the protagonist can provide for themselves. They can find comfort in knowing that their own presence will be constant in their life, no matter where they end up. This reading of the symbol of the owl is crucial to the purpose of the manuscript, as, given the desired purpose of inspiring young minds like May, this demonstrates to readers that they are never truly alone.

The owl could also be seen as a symbol of May herself. Since May was an advocate for young, female artists to pursue their dreams of learning art through travel, one may view May as the owl, in that women can turn to her travel writing for support. May's writing can offer guidance, motivation, and inspiration for those in a similar position. This is historically remarkable, as when May first began her art journey, she did not have access to the sort of support that she herself provided for women like her (Dabbs Author). This relates back to the owl, as the owl provides the protagonist with the support that May offers to her readers. Despite the example discussed above, readers will form their own opinions surrounding the symbolism of the owl upon in-depth analysis. The open-endedness of the text is what allows for such a unique manuscript.

By exploring the background of May, readers can understand the significance of the manuscript and anchor the plot, matching certain events to the author's life.

Bibliography

- Alcott, Louisa May and May Alcott Nieriker, Little Women Abroad: The Alcott Sisters' Letters from Europe, 1870-1871, ed. Daniel Shealy, University of Georgia Press,

- Dabbs, Julia K. "Empowering American Women Artists: the Travel Writings of May Alcott Nieriker" Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide, Vol. 15, No. 3, Autumn

- ---, May Alcott Nieriker, Author, and Advocate: Travel Writing and Transformation in the Late Nineteenth Century, Anthem Press,

- Fink, Lois M., American Art at the Nineteenth Century Paris Salons, Cambridge University Press,

- Flint, Azelina and Hehmeyer, Lauren, The Forgotten Alcott, Routledge

- McElroy, Guy, Facing History: The Black Image in American Art, 1710-1940, Bedford Arts,

- Ticknor, Caroline, May Alcott: A Memoir, . Reprint. Applewood Books, n.d.