My Owl: A Passage from an artist's life abroad

And looking up at my owl always perched on the mantelpiece, I almost believed he winked his approval in answer to the inquiry he read in my eyes, as if to say "Yes I am tired of posing and disgusted with such low aims in art. Go and study the fine collections in this big city, copy the wonderful Turners, sketch on the Thames, paint anything but waste no more time buying bric-a-brac." "

Abigail May Alcott Nieriker

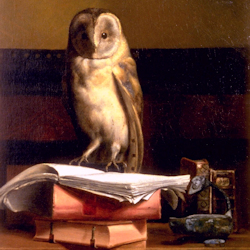

Still Life with Owl by May Alcott Nieriker, 1877. Oil on canvas. Used by permission of Louisa May Alcott's Orchard House

Still Life with Owl by May Alcott Nieriker, 1877. Oil on canvas. Used by permission of Louisa May Alcott's Orchard HouseIntroduction

My Owl is Abigail May Alcott Nieriker's charming

short story in which a taxidermized owl becomes a talisman for a

young artist trying to make her mark in the Parisian artworld. After

purchasing it in a Parisian bric-a-brac shop, the narrator paints a

still-life of it. Women artists of this period, like Nieriker, were

expected to be copyists and still life painters only. This stifled

their ambitions to become well-known artists because of the

Hierarchy of Genres

, which defined types of art

in levels of superiority. Still life and animal paintings were at the

bottom of the genre hierarchy (Butterfield-Rosen, 73-4), reducing the

chances of having them displayed at the most

prestigious exhibition forum

(Garb, 26), the

Paris Salon, which was the official exhibition of

the Beaux-Arts Academy. In My Owl, the

protagonist's owl painting is chosen for the Salon. The

contradiction of a decidedly low-brow genre painting being in a

significant exhibition places the owl at the forefront of the

narrative. Nieriker's choice of the owl deliberately evokes a

myriad of symbols, which this introduction will explore. The

owl's symbolism is open-ended, yet clearly represents the

speaker's artistic growth and inner psyche, and markedly

encapsulates Nieriker's sisterly relationship.

The taxidermized owl is unquestionably the tangible manifestation of

the speaker's psyche. Historically, owls have been

representations of introjection, projection, and other mental

phenomena (Fernandes), commonly appearing in dreams and other aspects

of the projector's subconscious. For example, the Ancient Greeks

believed owls were reflections of mythological wisdom, as seen in

Book XIV of the Iliad, where Hypnos, disguised as an

owl, is sent to turn the tide of the Trojan War (Homer). In a similar

way, Nieriker's owl turns the tide in the speaker's

artistic career, gaining attention by being displayed in the

notoriously unattainable Parisian Salon, where the painting queerly

hangs among the numberless nude subjects on the

walls

(Nieriker). Similarly to Homer's veiled deity, an old

folkloric Siberian legend portrays owls as good spirits who help and

guide people, especially travellers who wish to reach particular

destinations (Weinstein). This legend increases the significance of

the owl as a journeying companion in Nieriker's travel

narrative. Furthermore, in some areas of India, not only is the owl

seen as the Vahana, a divine vehicle in the Hindu religion for a

goddess to bring prosperity, but its meat itself is widely consumed

as a natural aphrodisiac (Weinstein), possibly reflected in the

owl's fate which catalyses the romance between the speaker and

the man who tries to save it.

The owl also establishes a dichotomy through vast parallelism in the

relationship between Abigail May Alcott Nieriker and her sister

Louisa May Alcott. In the text, the

speaker's taxidermized owl leads her to become a celebrated

woman artist by acting as a muse for her creativity, and also through

its humanistic offerings of guidance, for example when it tells her

to go and study the finer collections in this big

city

(Nieriker). The personification of the owl magnifies its

ability to express intelligence far beyond other

avian species

(Morris). This offering of counsel reflects

Nieriker's professional relationship with her sister. Louisa May

Alcott used the fame she received after publication of

Little Women to illuminate the work of Nieriker,

regardless of accreditation of work. This highlights a fascinating

duality between independence and reliance. The concluding scene of

My Owl is symbolic of finality, the ability to progress

from her interlinked state with the owl - still offering gratitude to

it yet allowing herself to evolve independently. This highlights

Nieriker's absence of freedom from Louisa's prominence in

the literary field, yet acknowledges her role in Nieriker's

journey to literary and artistic prominence, allowing Nieriker to

maintain her artistic independence.

Across a range of mythologies, the owl represents two sides of a

spectrum - either a sign of good fortune and wisdom, or connected to

poor health and witchcraft. In My Owl, Nieriker's

owl combines the positive connotations seen across the owl's

history with a representation much more personal to her (Lewis). As

previously explored, the owl brings good luck and wisdom, somewhat

enlightening the speaker's work. However, it also represents her

desire to stand out among the other female artists of the time, just

as the owl was discovered among other effects of

some artist

(Nieriker). The owl's role develops throughout

the story, going from representing Nieriker's desire to become

a successful artist, to being her muse, to being the mentor she

outgrows - essentially representing the removal of metaphorical

training wheels when the owl is 'killed'. The owl morphs

and changes as the speaker needs it to, representing each stage of an

artist's journey in each stage of the piece.

The symbolical interpretation of the owl is ambiguous, ultimately

foreshadowing the entirety of Nieriker's interdisciplinary

career. My Owl, similar to many of the other travel

narratives Nieriker wrote, was never published. Though a

New Criticism approach, where the interpretation

of the owl's symbolism through a structure of

interlocking motifs

(Frye, 82), expands the reader's

perception of the short story's literary merit, a consideration

of the autobiographical, cultural, and historical aspects presents a

feasible image of Nieriker in future academia. This rebirth of a

forgotten artist through literary criticism itself is a symbol of a

new era of remembering and reimagining female and interdisciplinary

artists. Bullington suggests that Nieriker's full artistic merit

did not flourish because of the culturally transitional period for

women, writing that historians and scholars largely forgot Nieriker

because she was a transitional woman (196). Despite being mostly

overlooked, transition ultimately 'makes the product' -

signifying an overarching transformational element that is prevalent

in the artwork of this period, just as the owl is the catalyst for

transformation in the life of the narrator.

Bibliography

- Bullington, Judy, "Inscriptions of Identity: May Alcott as Artist, Woman, and Myth", Prospects, Vol 27, , pp. 177–200

- Butterfield-Rosen, Emmelyn, "The Hierarchy of Genres and the Hierarchy of Life-Forms", Res, Vol 73-74, No 1, , pp. 77–93

- Frye, Northrop, "Second Essay: Ethical Criticism: Theory of Symbols", Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays, Princeton University Press, , pp. 71-128

- Garb, Tamar. Sisters of the Brush: Women's Artistic Culture in Late Nineteenth-Century Paris, Yale University Press,

- Homer, Iliad, tr. Peter Jones, Penguin,

- Lewis, Deane, "Owls in Mythology and Culture", The Owl Pages, <https://www.owlpages.com/owls/articles.php?a=62> [accessed ]

- Morris, Desmond, Owl, Reaktion,

- Nieriker, Abigail May Alcott, "My Owl", An Artist's Holiday, , transcribed by Azelina Flint, [accessed ]

- Weinstein, Krystyna, The Owl in Art, Myth, and Legend, Grange Books,

- Wilson Fernandes, Julio, Jung Journal, Taylor & Francis, <https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/ujun20/16/1> [accessed ]